In 1913, after two terms as the president of the United States, Theodore “Teddy” Roosevelt, an avid hunter, explorer, and naturalist, decided to take on the most dangerous adventure of his life – to explore and map the course of the Rio da Duvida (River of Doubt) through the Pantanal wetlands of southwestern Brazil. The expedition was repeatedly plagued by bad luck. Cannibalistic natives continually shadowed their movements and treacherous rapids overturned their canoes, drowning paddlers and sweeping away precious supplies. At one point, Roosevelt contracted a flesh-eating bacteria that weakened him so much that he implored his son to leave him behind to die. Ultimately, Roosevelt escaped back to civilization but died three years later from malaria.

Today, there is no malaria, no ferocious rapids nor any salivating cannibals in the Pantanal, just a wildlife watcher’s paradise. Fourteen years ago, when I visited the area for the first time I was not prepared for the resplendent color of the toucans and parrots, the elegance of the herons, egrets and storks, the energy of the giant river otters tirelessly fishing for piranhas, the primeval magnificence of the basking caimans, the playful antics of the capybara, and the crimson beauty of the sinking sun as it cast rainbow hues across the rivers.

The Pantanal is a large freshwater wetland; home to nearly 500 species of birds including the magnificent endangered hyacinth macaw, as well as many of the large charismatic mammals of South America, including: howler monkeys, giant anteaters, giant river otters, coatimundis, collared tamanduas, Brazilian tapirs, crab-eating foxes and ocelots. The Pantanal also has the highest density of jaguars in the world. In recent years, daylight sightings of this mystical, powerful cat have become more frequent than ever. Seeing a wild jaguar, of course, is never a guarantee, but just knowing that such a glorious predator may be glimpsed as you round a curve in the river adds an unforgettable energy to the search.

The Pantanal is a large freshwater wetland; home to nearly 500 species of birds including the magnificent endangered hyacinth macaw, as well as many of the large charismatic mammals of South America, including: howler monkeys, giant anteaters, giant river otters, coatimundis, collared tamanduas, Brazilian tapirs, crab-eating foxes and ocelots. The Pantanal also has the highest density of jaguars in the world. In recent years, daylight sightings of this mystical, powerful cat have become more frequent than ever. Seeing a wild jaguar, of course, is never a guarantee, but just knowing that such a glorious predator may be glimpsed as you round a curve in the river adds an unforgettable energy to the search.

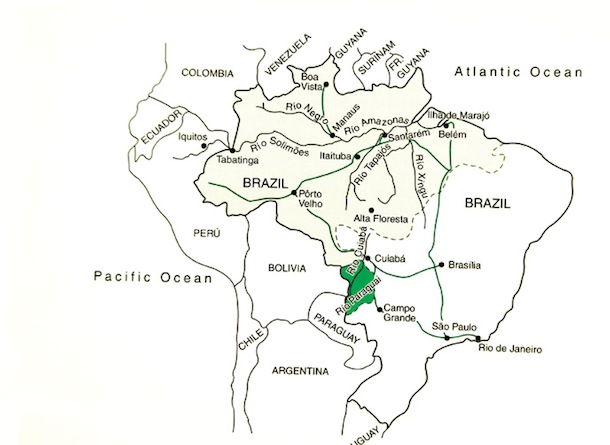

The Pantanal is located is the geographical centre of South America. Its area is greater than the combined areas of Prince Edward Island, nova Scotia and new Brunswick. In short, it’s a very big place. The Pantanal is an inland basin of savannah that floods during the summer rainy season; with as much as 75 per cent of the entire area becoming inundated. There are really only two access points into the Pantanal; either through the city of Cuiaba in the north or through the city of Campo Grande in the south. I’ve traveled both routes and much prefer the northern approach where there are fewer cattle ranches, less human activity and a greater likelihood of seeing large mammals such as tapir, jaguar and deer.

The Pantanal is located is the geographical centre of South America. Its area is greater than the combined areas of Prince Edward Island, nova Scotia and new Brunswick. In short, it’s a very big place. The Pantanal is an inland basin of savannah that floods during the summer rainy season; with as much as 75 per cent of the entire area becoming inundated. There are really only two access points into the Pantanal; either through the city of Cuiaba in the north or through the city of Campo Grande in the south. I’ve traveled both routes and much prefer the northern approach where there are fewer cattle ranches, less human activity and a greater likelihood of seeing large mammals such as tapir, jaguar and deer.

Access into the Pantanal from the north is via the Trans Pantanal Highway. The highway, built in 1976, is a highway in name only. It’s actually just a narrow, rutted gravel road 160 kilometers in length that traverses all the main wildlife habitats in the northern Pantanal. Brazilian biologists informally call the highway the national Park of the Pantanal because it is so rich in wildlife.

There are really only two seasons in the Pantanal. The summer season extends from november to March when it rains, and rains, and rains. The roads become impassable and many areas are only accessible by boat or small private plane. The name Pantanal means “swampland” in Portugese. During the summer rains the water level can rise by five metres making the Pantanal the world’s largest freshwater wetland, four times the size of the legendary Okavango Delta in Botswana and eight times the size of the Florida Everglades. The winter season, from April to October, is the dry season characterized by warm temperatures and relatively low humidity. Unfortunately the winter is also the fire season when ranchers set the savannah ablaze. They start burning in July and it peaks in August. The smoky skies were an issue on my first trip to the Pantanal in September 1997. That year, one of my traveling companions was a professional photographer from France who spoke very little English but he knew one phrase very well and he repeated it often. “Shitty light, shitty light, shitty light.” The smoke can get so thick that authorities in Cuiaba may close the airport for days at a time. I’ve never seen it get that bad but the hazy, smoky skies can certainly make landscape photography challenging at times.

There are really only two seasons in the Pantanal. The summer season extends from november to March when it rains, and rains, and rains. The roads become impassable and many areas are only accessible by boat or small private plane. The name Pantanal means “swampland” in Portugese. During the summer rains the water level can rise by five metres making the Pantanal the world’s largest freshwater wetland, four times the size of the legendary Okavango Delta in Botswana and eight times the size of the Florida Everglades. The winter season, from April to October, is the dry season characterized by warm temperatures and relatively low humidity. Unfortunately the winter is also the fire season when ranchers set the savannah ablaze. They start burning in July and it peaks in August. The smoky skies were an issue on my first trip to the Pantanal in September 1997. That year, one of my traveling companions was a professional photographer from France who spoke very little English but he knew one phrase very well and he repeated it often. “Shitty light, shitty light, shitty light.” The smoke can get so thick that authorities in Cuiaba may close the airport for days at a time. I’ve never seen it get that bad but the hazy, smoky skies can certainly make landscape photography challenging at times.

The best season for wildlife photography, despite the potential for smoky skies, is during the winter dry season, April to October. As the Pantanal slowly dries out, water holes become concentrated with fish, especially piranhas and catfish, offering a feast for hungry herons, egrets, and storks. Jacare caimans, relatives of the alligator, may cluster in such great numbers, that they represent the largest aggregation of these scaly beasts in the world. As river levels drop, travel by flat-bottomed boat can yield photos of capybaras basking along the banks, kingfishers, storks and herons stalking the shorelines, giant otters hunting in the shallows, and if you are lucky, a glimpse of a jaguar or a tapir.

Ninety per cent of the Pantanal is privately owned, and over 80 per cent of it is devoted to cattle ranching. until 1990, the Pantanal was an obscure, little-known corner of Brazil. That year Brazilian television broadcast el Pantanal, a soap opera about the trials and tribulations of a ranching family in the southern Pantanal. Overnight, this forgotten corner of Brazil became famous. Viewers tuned in each week for glimpses of the natural beauty of the area. But nature was probably not the strongest lure to viewers as the show introduced frontal nudity to Brazilian television for the first time and had an appealing supernatural storyline in which a jaguar is reincarnated as a beautiful woman who falls in love with a handsome cowboy. Now, that’s good television. As a consequence of the publicity, visitor numbers increased dramatically and the trend continues today. Currently, over 100 ranches are involved in ecotourism, many offering trails, boats, guides, meals and accommodations. Don’t think you’ll be roughing it, as many lodges on these ranches are very comfortable, complete with swimming pools, air conditioning and a fully stocked bar.

Independent travel in the Pantanal is difficult unless you speak Portugese, so a tour group of some description is the best option. I’ve traveled to the Pantanal four times, most recently in April 2011, and in every case I traveled with Paulo Boute, the owner of Boute Expeditions. Paulo is simply the best guide imaginable. He knows the wildlife intimately, he understands the needs of photographers, and he is an indefatigable source of energy and good spirits. I recommend him highly.

Photography situations in the Pantanal are quite varied. Sometimes you will photograph from a vehicle in which case a bean bag is helpful for stability, sometimes from trails, and often from flat-bottomed boats. In both of the latter cases I use a tripod. The big draw in the Pantanal is wildlife, so large telephoto lenses in the range of 300-600 mm guarantee the best results. Telephoto lenses with image stabilization are even better, especially when you are shooting from a rocking boat. For the macro photographer there is a great variety of flowers, and a great range of insects from metallic beetles to rainbow-colored butterflies.

Photography situations in the Pantanal are quite varied. Sometimes you will photograph from a vehicle in which case a bean bag is helpful for stability, sometimes from trails, and often from flat-bottomed boats. In both of the latter cases I use a tripod. The big draw in the Pantanal is wildlife, so large telephoto lenses in the range of 300-600 mm guarantee the best results. Telephoto lenses with image stabilization are even better, especially when you are shooting from a rocking boat. For the macro photographer there is a great variety of flowers, and a great range of insects from metallic beetles to rainbow-colored butterflies.

Brazil will host the 2016 Summer Olympics and the government is already planning to pitch the legendary Pantanal wetlands as an exciting side destination for adventurous visitors. The Pantanal is not a destination for every nature photographer, but if you like the idea of visiting an area that is relatively undiscovered, a paradise for large colorful birds, and the haunt of magical beasts like giant anteaters, anacondas and jaguars then it’s for you.

Article by Wayne Lynch

| PHOTONews on Facebook | PHOTONews on Twitter |