In May 2023, my wife Aubrey and I spent three weeks camping in the southern Okanagan Valley in British Columbia. Our quest was to explore, hike, and photograph the wild lands west of the town of Osoyoos where Parks Canada is hoping to locate the country’s latest protected natural region, the South Okanagan-Similkameen National Park Reserve. The coveted landscape features grassy rolling hills, sweeping valleys, conifer forests, and sagebrush flats. This unique, semi-arid environment sits on the northern edge of the Great Basin Desert of North America and is recognized as one of the most endangered ecosystems in Canada, and one yet to be protected by a national park.

Much of the proposed park area is a mixture of grassy slopes, expansive stands of aromatic sagebrush, vanilla-scented ponderosa pines, and shady woodlands of leafy poplars.

I first visited the Okanagan some 40 years ago. Today, only scattered fragments of the original natural beauty of the region remain, since much of the valley has been methodically and thoughtlessly destroyed and replaced by vineyards, golf courses, vacation condos, and other superfluous developments. The idea of a national park in the Okanagan Valley was first proposed roughly 20 years ago, and if ever there was a need for such a park, it is now.

Unfortunately, in late July, two months after our visit, a massive wildfire swept across the border from Washington state burning a large area within the boundaries of the proposed national park. Today, these areas are closed to visitors to allow the area to regenerate and recover.

Below are some of my favourite images celebrating the beauty and wildlife richness of this diverse ecosystem.

The showy yellow blossoms of arrow-leaved balsamroot provide an early-spring splash of colour to dry hillsides.

When I took this photograph I had been hiking the area for over six hours and never saw anyone, much to my surprise and delight.

The mountains visible in the distance are in Washington State. The southern boundary of the future park will begin at the international border.

The long-tailed weasel is a predator of open country that preys on mice, voles, pocket gophers, and nesting birds although it will occasionally tackle cottontail rabbits that weigh more than it does.

These yellow-bellied marmots, which had recently emerged from hibernation, were nuzzling each other on the rocky slope where they had spent the winter.

In British Columbia, the American badger is an endangered species because of habitat loss from human development. The Okanagan and Similkameen Valleys are two of the few areas where this rodent-hunting weasel still occurs.

The California quail was introduced into the Okanagan Valley in the early 1900s and has since become abundant and widespread. The male’s ornamental topknot which looks like a single feather is actually a cluster of six separate feathers.

Male mountain bluebirds are highly aggressive and defend their nest territory with chases and aerial displays in which rival males hover in front of each other, flashing the intense blue in their plumage as they rapidly open and close their wings.

Male and female bluebirds adjust the size of the prey they deliver to nestlings based on the gape size of the chicks, bringing smaller items initially and larger ones as the chicks get older. The male in the photo is delivering a noctuid moth to his clutch of four chicks.

The intense blue colouration of the male western bluebird, as well as that of the mountain bluebird, is not produced by pigmentation. Rather, it is created by the reflection of sunlight on the microscopic structure of the bird’s plumage.

This western bluebird was nesting in an old woodpecker hole in a decaying aspen poplar. Above it there was a pair of nesting tree swallows and on the trunk below it there was a pair of house wrens. The tree was a virtual avian condominium.

The iridescent burnished copper gorget of the male rufous hummingbird is its most distinctive physical feature. With a temperament as fiery as his plumage he will attack any intruder into his territory including sparrows and thrushes as well as squirrels.

The flying capabilities of hummingbirds are among their most notable achievements: wingbeat rates of 200/second, power dives up to 100 kilometers/hour, and a capacity for prolonged hovering and rapid backward flight. These flying feats are possible thanks to hummingbirds having the largest relative breast muscles of any group of birds (weighing up to 30% of their total body weight), the largest relative heart size of any vertebrate, and heart rates up to 1,200 beats/minute.

At the start of nest building and egg laying, the male rufous hummingbird abandons his mate and flies to the nearest alpine meadows to take advantage of the nectar-rich flowers.

The calliope (pronounced Kall-EYE-oh-pee) hummingbird, weighing a mere 2.8 grams (less than the weight of a Canadian nickel) is not only the smallest breeding bird in North America, but it is the smallest long-distance migrant, travelling up to 8,000 kilometres annually to and from its winter home in Mexico.

The male lazuli (pronounced LAZ-yoo-lie) bunting, which is smaller than a bluebird, spends most of its time foraging inconspicuously for insects, spiders and seeds on the ground and in thickets.

The male lazuli bunting is a tenacious songster; singing as vigorously in the heat of the afternoon when most other songbirds are sensibly enjoying a siesta as he does in the cool of the morning.

The common poorwill hunts at night capturing moths and other flying insects on the wing. When this migratory bird is in Canada between April and September it can periodically slip into a deep torpor where its body temperature drops from a normal 40°C (104°F)to a mere 5°C (41°F) and remain “chilled out” for up to 36 hours. Doing so saves the bird valuable energy when temperatures are cool or insect prey are scarce.

The unwary Say’s phoebe (pronounced FEE-bee) is a typical flycatcher that hunts from a perch and waits for insects to fly past.

This cluster of western rattlesnakes (count them) was lying outside the cleft in the rocks where they had spent the winter together.

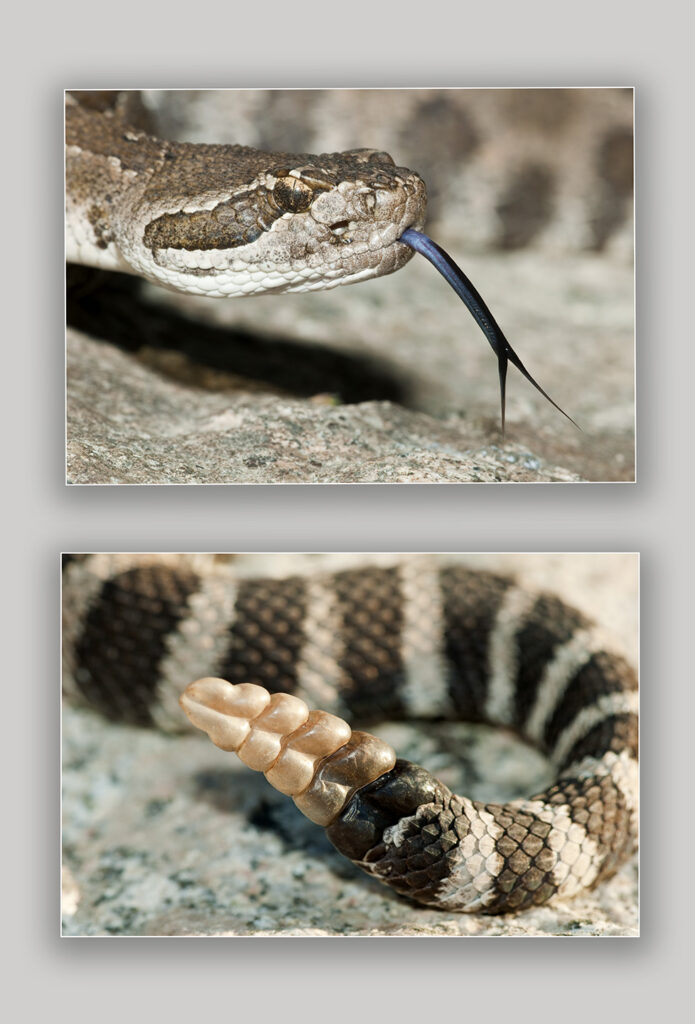

The western rattlesnake, also known as the northern Pacific rattlesnake, is actually quite a timid creature and normally does everything it can to stay out of your way. This individual had climbed up onto the rocks to heat itself in the spring sunshine.

The two business ends of the rattlesnake: the head end which contains the heat-sensing facial pits, odour-tasting tongue, and its two hinged venomous fangs, and the tail end with its four loose segments which can be rapidly vibrated to produce a warning rattle.

The rubber boa is a small, secretive, nocturnal snake that gets its name because of its plasticine-like appearance. The snake is a miniature member of the famous boa family best known for its larger tropical relatives such as the boa constrictor that may grow over three metres (9.8 ft.) long and weigh over 27 kilograms (60 lbs).

When handled, the beautiful, docile rubber boa never bites and often coils peacefully in your hand. The inoffensive snake will sometimes curl into a ball, hiding its head beneath its body as this one is doing and conspicuously exposing the blunt tip of its tail that looks remarkably like a second head.

The pygmy short-horned lizard, the smallest of the 13 horned lizard species in North America, was last seen in the Okanagan more than 100 years ago and is assumed to be extirpated. I travelled south into neighbouring Washington State to photograph this endearing little reptile.

The biologist who guided me to the lizard also brought along her infant son who made a convenient model to show scale.

The long-toed salamander is the most widely distributed salamander species in British Columbia yet it is rarely seen as it spends most of its time underground or beneath rocks or fallen trees.

The elusive tiger salamander, one of the largest salamanders in North America, growing up to 32 centimetres (12.5 in.) in length, eats earthworms and insects as well as the occasional frog, toad, or baby mouse.

The handsome Lewis’s woodpecker behaves more like a flycatcher than a head-banging, bark-chipping woodpecker, often flying out from a perch to catch insects on the wing.

This pair of Lewis’s woodpeckers had just finished mating. The pair had a nest hole in a nearby dead Ponderosa pine where they would likely lay 6-7 white eggs and incubate them for two weeks.

There are a number of small lakes scattered within the proposed park boundaries. The lakes are used by many duck species including cinnamon and green-winged teal, redheads, ruddys, ring-necks, and Barrow’s goldeneyes.

The handsome male Barrow’s goldeneye is high on the “wish list” of birdwatchers from eastern Canada, and it was high on my photo target list as well. The photograph is just a simple portrait but it’s the first one I have taken of this species.

I never pass up an opportunity to photograph the male yellow-headed blackbird and the Okanagan teased me with this one.

Canadian tiger swallowtail butterflies were everywhere in the park area and they were hard to resist.

About the Author – Dr. Wayne Lynch

For more than 40 years, Dr. Wayne Lynch has been writing about and photographing the wildlands of the world from the stark beauty of the Arctic and Antarctic to the lush rainforests of the tropics. Today, he is one of Canada’s best-known and most widely published nature writers and wildlife photographers. His photo credits include hundreds of magazine covers, thousands of calendar shots, and tens of thousands of images published in over 80 countries. He is also the author/photographer of more than 45 books for children as well as over 20 highly acclaimed natural history books for adults including Windswept: A Passionate View of the Prairie Grasslands; Penguins of the World; Bears: Monarchs of the Northern Wilderness; A is for Arctic: Natural Wonders of a Polar World; Wild Birds Across the Prairies; Planet Arctic: Life at the Top of the World; The Great Northern Kingdom: Life in the Boreal Forest; Owls of the United States and Canada: A Complete Guide to their Biology and Behavior; Penguins: The World’s Coolest Birds; Galapagos: A Traveler’s Introduction; A Celebration of Prairie Birds; and Bears of the North: A Year Inside Their Worlds. In 2022, he released Wildlife of the Rockies for Kids, and Loons: Treasured Symbols of the North. His books have won multiple awards and have been described as “a magical combination of words and images.”

Dr. Lynch has observed and photographed wildlife in over 70 countries and is a Fellow of the internationally recognized Explorers Club, headquartered in New York City. A Fellow is someone who has actively participated in exploration or has substantially enlarged the scope of human knowledge through scientific achievements and published reports, books, and articles. In 1997, Dr. Lynch was elected as a Fellow to the Arctic Institute of North America in recognition of his contributions to the knowledge of polar and subpolar regions. And since 1996 his biography has been included in Canada’s Who’s Who.