As I write these words I’m parked in a Toyota Land Cruiser above the muddy banks of the Mara River in southern Kenya, just a few kilometres north of the Tanzanian border. Less than an hour ago, the horizon released the flaming eye of the rising sun and I’m bathing in the warm embrace of the sun’s first rays. As I wait, I’m not alone. A small cluster of white-backed vultures, roosting in the nearby trees, is also waiting, but waiting is what vultures do best. A swirl in the water catches my eye and I recognize the languid sweep of a crocodile’s tail. When I look closer, I count five of the scaly beasts drifting between the riverbanks like guests at a reception, waiting for the buffet to be served. On the far side of the river, less than two hundred metres away, hundreds of wildebeests, along with some zebras, shuffle around in a thick cloud of amber dust. The wildebeests and the zebras are also waiting; waiting for one or more among the throng to be hungry enough, impatient enough, or naive enough to plunge across the river to reach the green flush of oat grass all of them can see, and probably smell. I try not to take my eyes off the herds for more than a few moments at a time because I know from past experience that a river crossing can begin without warning: the action changing suddenly from milling to mayhem.

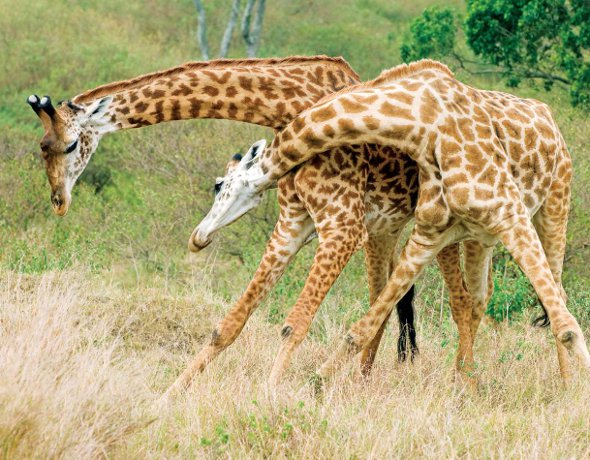

In an instant it happens. A trio of adult zebras leaps into the coffee-colored waters and swims powerfully across the river. The suddenness of the event and the splashing and braying of the zebras seems to immediately infuse the waiting wildebeests with courageous resolve, and wave after wave of their ranks plunge into the river. The noise, the dust, the determination, and the wildness in the animals’ eyes imbues the moment with a primal feel and I purposefully stop photographing to fully savour the beauty of this ancient natural event. When the knobby head of a crocodile erupts from the foam I snap back into action but the resulting photograph fails to capture the flailing legs of the drowning wildebeest or the underwater struggle that precedes it. The crossing is over in less than ten minutes. Several wildebeests have been captured by the crocodiles, but hundreds have escaped, and the survivors will fatten on the fresh green grass around me. Before the morning concludes I photograph a gaggle of vultures squabbling over a carcass, a pair of male giraffes wielding their heads like sledgehammers in a contest of neck wrestling, a newborn Thomson’s gazelle nursing on shaky legs, and a stately secretary birdstomping a fleeing cobra, then swallowing the battered serpent in a single gulp. Such is a day in the Serengeti, one of the greatest wildlife locations on the planet.

The name Serengeti is derived from the Masai language and means a wide open space. Nowhere else on Earth can a person see such an incredible array of wildlife: 1.3 million wildebeests, 200,000 plains zebras, 440,000 Thomson’s gazelles, 100,000 impala, 200,000 topi, hartebeests, and African buffalo, plus scores of a dozen other kinds of hoofed mammals. Then there are the predators: 7,500 spotted hyenas, 3,000 lions, 1,000 leopards and several hundred cheetahs. When I was in East Africa this past September the density of predators had attracted film crews from the British Broadcasting Corporation, Disney Nature and National Geographic: all striving to capture the visual splendour of the Serengeti.

The Serengeti ecosystem, at 25,000 square kilometres (9,600 sq. mi), is just a bit larger than the combined size of Jasper, Banff, Kootenay, Yoho and Waterton National Parks in Canada’s Rocky Mountains. This rich ecosystemis a mixture of open plains, acacia woodlands, and forest-rimmed rivers. Eightyfive percent of the Serengeti is located in Tanzania, centred around Serengeti National Park; the remainder is in southern Kenya, mainly in the Masai Mara Game Reserve.

The Serengeti is best known for its annual migrations of wildebeests, zebras and Thomson’s gazelles in numbers that defy the imagination. The animals move around in response to geographical differences in rainfall, which produces differences in the amount of fresh green grass available for them to eat. From December to March, the great herds are clustered in the southern Serengeti in Tanzania, and then from August to October they concentrate in the north in the Masai Mara Game Reserve in Kenya. Outside of these months the animals are in transit, migrating between the two key areas.

Most visitors to the Serengeti travel as part of an organized safari. As a photographer, your number one consideration is whether the safari is a general interest tour or a specialized photo tour. In the past year, at least half a dozen people have asked me why they should travel to East Africa on a photo tour instead of a general nature tour. They asked. “Doesn’t every tour focus on the streaming herds, elephants and lions?” “Why are photo tours generally more expensive than standard tours, and do you need to be an expert photographer to join a photo tour?” Here are four compelling reasons why a photo tour is the only way to visit the Serengeti if you’re an avid shutterbug.

Optimal Scheduling of Daily Programs

Every photographer knows that early morning and late day are the times when the light is most appealing for capturing everything from landscapes to leopards. That often means early wake up calls, breakfast in a box, and late evening dinners. On many of the general interest safaris the daily schedule revolves around dining room hours at the whim of the lodges. Little consideration is given to when the light is optimal for photography.

Extra Room in the Vehicles

To reduce the cost of a tour, many safari operators assign just one seat for each passenger. Typically, the brochure simply states that the tour features “modern, comfortable, minibuses” or “spacious 4-wheel drive vehicles”.

What they don’t tell you is that you will be packed inside like sardines, each person cradling his or her camera gear on their lap with their water bottle jammed between their knees. In the Serengeti, the standard mini-bus or Land Cruiser holds eight passengers, squeezed shoulder to shoulder, half of whom must photograph through the grime of a dusty window.

On a specialized photo tour each vehicle generally carries only three or four passengers. In this way, everyone has elbow room to photograph all at once, and fewer photographs are ruined by people jumping up and down from their seats, jiggling the vehicle. In short, on most photo tours you get at least two seats for every person, one for your bottom and another for your camera bag.

Time Spent With the Subjects

Photographers are generally very patient people who never mind waiting, sometimes for hours, to capture exciting light or unusual behaviour with their cameras. A tourism study done in Kenya in the 1980s determined that the average tourist spent just three minutes watching the first lion they saw on a safari, and once they had seen three lions they didn’t stop to watch any others. You can imagine the frustration a photographer would feel being trapped in such a vehicle because every encounter has something different to offer.

Leaders Who Are Photographers

Tour leaders who do not photograph cannot appreciate the difference that a bend in the road can make to the strength of a composition, the importance of the last 30 minutes of light at the end of the day, or the patience needed to wait for a catch light in the eye of an eagle. Many years ago, I co-led a photo tour to Costa Rica with a local leader who was reputed to be one of the finest naturalists in the country. Indeed, this pleasant man knew his birds, his plants, and his beetles, but he knew nothing about photography and the interests of photographers. When we stopped for a pleasing shot of a tropical landscape he argued that the parking lot around the next corner was better. It never was. When we stopped for the twentieth time in a day he protested that we would be late arriving at our daily destination. We never were. And when we stopped to photograph some cowboys, he said it wasn’t safe, yet their smiles and laughter told us that it was. Without my intervention, this skilled and knowledgeable local guide would have turned our photo tour into a photo failure.

A question that everyone has before a photo tour to Africa is “what equipment will I need?” Bring at least two camera bodies, three is better, in case one breaks or fails. For wildlife, the most useful lenses are medium telephotos in the 100 to 300mm range. If you like to photograph birds then you will need something bigger, in the 400 to 600mm range. Wide angle lenses are also a must to capture landscape scenes. (Tip: If you own backup lenses, bring them along in case your primary lenses get broken or malfunction). Surprisingly, an electronic flash is also very handy to have. With the development of low noise digital sensors which permit the use of high ISO settings I end up using an electronic flash to fill the shadows many times during a typical safari. Generally, tripods and/or monopods are useless in the cramped confines of the vehicles from which you will do the vast majority of your shooting. The best way to stabilize your camera is to use a bean bag.

Storing images is another issue that plagues every travelling photographer. On my last safari to the Serengeti I polled 20 photographers to see how many images they had shot on a two-week photo tour. The average was between 75 and 100 gigabytes, with one fellow shooting a remarkable 325 gigabytes. He confessed that he had shot over 17,000 images. I was happy it was him who had to edit those photographs and not me. My usual storage routine is to download everything onto a laptop and then back up all the images on a small external hard drive. A safari to the Serengeti will be one of the most expensive photo trips of your life. With good advance planning and careful tour selection I can guarantee it will be also be one of your greatest photographic experiences.

Follow Wayne’s adventures at his website – www.waynelynch.ca and don’t miss his latest book – Planet Arctic – Life at the Top of the World – now available online and through better bookstores everywhere.

| PHOTONews on Facebook | PHOTONews on Twitter |