Twenty-one times over the past three and a half years, renowned Ottawa photographer Michelle Valberg has stepped out of her comfort zone and into the Arctic. She’s taken over 90,000 photographs, shown her work at a three-month solo exhibition at the Canadian Museum of Nature and is working on her third book, Arctic Kaleidoscope… The People, Wildlife and Ever- Changing Landscape, due out in November 2012. We asked Michelle about her Arctic adventures and the challenges of photographing in the far north.

We could see him from the air—a 1000 lb polar bear nosing around on the kelp at low tide. He looked up at us as our pilot circled before landing the Turbo Otter on the rough, 200-ft tundra runway just south of Arviat in Nunavut. Thrilled, I ripped off a few quick photos of him and thought, ‘Not bad. First sighting and we haven’t even landed. Unreal.’

Taken with a 500mm lens on Polar Bear Alley at the Arctic Kingdom cabins near Arviat, Nunavut. I was too close for a full body shot (we were only 20 feet away), this is a full frame image without any cropping.

Only a few minutes later, it got a whole lot more real. As we unpacked the plane and prepared to truck our gear to the cabins that would be our home for the last part of October, 2011, my friend Leanne spotted the polar bear coming our way. We had our Inuit guides to keep us safe for such encounters, but even so, we were scared. And exhilarated.

Slowly, curiously, he approached closer and closer. I snapped a few more shots and realized that at this range, I couldn’t even get a full body image. Suddenly, he dropped his head and flattened his ears, ready to charge. I took another photo. “I’m gonna have to take a ground shot to scare him off,” whispered our guide Jason. “Okay with that?” I nodded, wide-eyed.

After the shot, the bear moved off. Close encounter? Maybe. But over my past 21 trips to the Arctic to photograph the astonishing variety of wildlife, flora and people, close encounters have been surprisingly common. Believing that the Arctic is a white, barren and cold land—and sometimes it is—we don’t always open our eyes to the vast landscape and its abundant wildlife. We also forget that this environment—desolate, haunting and compelling as it is—requires a different mindset. I had to learn to be patient, be quiet and listen – really listen. In the city, I find our senses are more filtered. In the Arctic it is different. you feel raw and exposed to every breath of wind, every noise. you can hear animals breathe and if you wait long enough and if you are lucky, you can get close enough to smell them.

Within my first few trips, I’d photographed bears, muskoxen and everything in between, but never a walrus. Then, late in the fall of 2010, I heard about a large group of walrus near Hall Beach, Nunavut. By large, I mean 10,000 animals, piled on top of each other,barking, fighting, eating and writhing like a leathery, living carpet.

My first view—and smell—of the walrus herd was from a fishing boat our guide used to get us close to the sandy beach where they were located. Some swam gracefully and athletically close to the boat before we docked and trudged up a hill overlooking their beach. They’d often be diving down into the water to eat clams.

Shot after shot, I captured them arguing, jostling and awkwardly moving their massive bodies. The gagging smell—the worst barnyard odor imaginable—was overpowering. Our second day, we moved very slowly along the beach, creeping incrementally so we wouldn’t startle them. Sometimes, one would edge to the water and dive in, followed by hundreds of others. Eventually, I stood three feet away from a massive, 2000lb bull that lay at the fringe of the herd. We stared eye to eye. I will never forget that moment of full comprehension of who he was and the wonder of me being there.

My love affair with the Arctic began with a fateful call almost four years ago to David Reid, the owner of Polar Sea Adventures in Pond Inlet. David recommended that I see the floe-edge, where the sea ice meets the open water and all wildlife gathers in the spring at ice break-up. you name it, they come: polar bears, walrus, seals, narwhal, beluga, bowhead whales and birds congregate because of the microcosms that live below the ice surface. During our eight days on the ice, we’d stand quietly on the floeedge, waiting, watching and listening. It was life-changing and a photographer’s paradise.

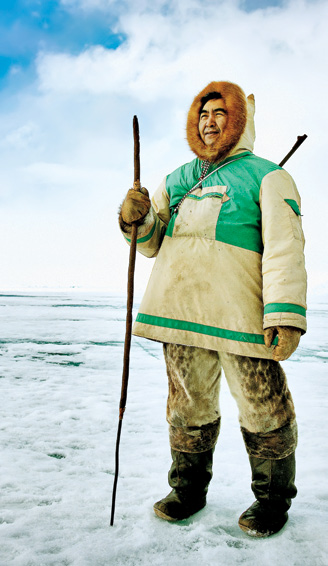

While on the Arctic Bay, Nunavut floe-edge with Arctic Kingdom, we met this hunter. He brought over a seal he had just caught to share a meal with our group.

Weather can pose special issues for photographers. I photographed my first polar bear—curiously sniffing with his nose in the air—on a cold, windy day. I was digiscoping with my Kowa telescope, but the wind buffeted the scope and camera, making it hard to hold steady, even on a tripod. These days, higher ISO capabilities in the newer digital SLRs allow us to use a much faster shutter speed with less noise issues. For shots with a scope, I like to keep the shutter speed around 1/2500 second, so lighting conditions have to be good. I carry two cameras with me at all times—a Nikon D3S with either a 14-24mm or 24-120mm lens, so I have a wide angle option and I can easily switch to video mode —and a Nikon D3X, with a 200-400mm and 2x extender for shooting wildlife. Flexibility is important: a narwhal can appear right in front of you, while in the distance a 70 ton bowhead whale is breaching. Having two cameras means you can catch it all without juggling lenses or having snow and Arctic air blow into the camera during a lens change.

The other challenge is staying warm when you’re standing still. In other words, good gear is critical. Personally, I don’t go anywhere without my Canada Goose parka with maybe the exception of July and August months. Toasty, flexible gloves and lots of layers are also key. And when it comes to managing equipment, my advice is this: keep your batteries in a inner pocket close to your body, have cleaning cloths at easy access, especially in cold weather when the lenses are vulnerable and you’re more likely to fog up, and avoid condensation issues by keeping your cameras in plastic bags for a couple of hours when transferring from cold to warm temperatures. I use 32 gig cards. Both of my cameras have double card slots—it helps not having to change my cards during a full day of shooting. Luckily, in most situations, we have a generator if we are on the land or ice, so charging the batteries has never been a problem.

Groups of up to 40 Narwhal would gather in the pools created by the pack ice on the floe-edge. We were so close we could hear them breath and sing. This was taken with my Kowa telescope and Nikon adapter.

More recently, I visited the floe-edge at Arctic Bay, Nunavut, this time with Arctic Kingdom. Day one – I photographed a polar bear eating a narwhal carcass just 100 feet from where we stood, captured images of king eiders in flight and came so close to pods of narwhal, I could hear them breathe and sing.

Determined to get even closer, I put on a dry suit and slid into the frigid Arctic waters with an underwater camera system. Despite being a good swimmer, I had no idea what to expect, aside from very cold hands.

I waited. And waited. Minutes before, narwhals were all around, but when I got in the water they disappeared. Eventually— fifty minutes later—my patience paid off. A narwhal was coming my way, I submerged my head, and there he was, just four feet beneath me. He stopped and turned upside down to take a better look. “Hey there beautiful,” I thought, as we made eye to eye contact. I turned and another six narwhal elegantly glided through the water towards me. I fired off a few shots, but to be honest, I was so excited, I had no idea if I was aiming in the right direction. Unfortunately, the weather turned and I wasn’t able to get into the water again on that trip. I can’t wait to go back and have another go.

A grandfather and grandson came down to greet us when we arrived by the Clipper Adventurer with Adventure Canada in Gjoa Haven, Nunavut.

But it is the magnificent, stately polar bear that keeps me going back. In August, I went in search of them through the Northwest Passage with Adventure Canada (I was the resource staff photographer). Starting in Greenland and ending in Kugluktuk (Coppermine), Nunavut, we found our quarry. As we arrived at Conningham Bay, we spotted 22 polar bears devouring Beluga whale carcasses on the shore. The fog was rolling in and the light was low as we took out the Zodiacs to get a better view. I used the edge of the Zodiac to steady my camera. It was exciting to shoot bears looking bloody, raw and fierce. Then, from the corner of my eye, I saw the most unbelievable and rare sight: four polar bears sparring in the water, with a fifth loitering nearby. Time was short, the light was low and the action was fast-paced, so I quickly changed my ISO to 1600 to get my shutter to 1/2000 seconds and got to work. Our ship had to make way through a very narrow strait while there was still light, so I shot countless frames in what little time I had.

The animals, the landscape, the grandeur of the north continue to call me back, as do the people. Their generosity, spirit and determination to live on their terms inspired me to give their communities back at least something of what they have given me. And so, over the past three years, I created Project North, a charity that brings hockey equipment to communities in Nunavut. Community sport is one of the most positive forces in young lives and I believe it’s a key factor in building life skills and social networks. So far, we’ve managed to deliver $300,000 in new hockey gear to 11 Nunavut communities. Our success is due to the generous support of First Air, KOTT North and the NHLPA Goals and Dreams Fund, amongst many others. Working in the north has given me an unexpected direction as a photographer. But it’s done much more. It’s given me scope as a Canadian. I remember standing on the floe-edge, staring out to sea and trying to comprehend the immense sky overhead, lit by the endless summer solstice. It was exotic and foreign, but my heart welled and I thought, “This! This is my country!”

Michelle Valberg currently has three exciting projects: her coffee table book, Arctic Kaleidoscope… The People, Wildlife and Ever-Changing Landscape, due out in November 2012; a children’s book called Ben and Nuki Discover Polar Bears due out in April 2012, and a gallery exhibition titled Arctic Kaleidoscope in New york City in April 2012.

For more information, please visit www.michellevalberg.com or www.valbergimaging.com. To find out more about Project North, please visit the website at www.projectnorth.ca. And to inquire about visiting and working in the north, contact Nunavut Tourism at www.nunavuttourism.com. Michelle will be the resource staff photographer on the Into the Northwest Passage trip with Adventure Canada from August 19-September 2, 2012.

If you had the opportunity to visit Michelle Valberg’s exhibition earlier this year at the Museum of Nature in Ottawa, you may have noted that all of the photos were printed on Hahnemühle Monet Canvas (100% cotton; fully archival). Michelle also uses Hahnemühle Photo Rag (also 100% cotton; fully archival) for her FineArt prints.

For more information contact:

www.arctickingdom.com

www.adventurecanada.com

www.polarseaadventures.com