Red Oak Leaves with Hoar Frost taken with Fuji Velvia film – Quebec – I always demanded professional quality from my work. Sadly, pro film adopted low ISO levels. Anything more than 100 ISO was considered too “grainy” to be used in publications. I normally used slide film like Kodachrome 64 or 25. But, with its vibrant colours, Fuji Velvia 50 ISO was my favourite.

Back in junior high school, I annoyed classmates with much mischief and a tiny camera – the antiquated Kodak Instamatic. With flash cubes, film cartridges, and compact size, it was easy to capture candid photos of unsuspecting students. In those days, film processing was necessary before viewing results. Meanwhile, my grandfather enjoyed instant gratification with his fool-proof Kodak Polaroid camera. He’d snap a frame, and like magic, we’d watch the image develop right before our eyes.

Gyrfalcon, taken with a Tamron 400mm F4 on Nikon FM2 – Ottawa – Almost all the analog lenses I used were manual focus. Fortunately, with practice and persistence, I managed to consistently capture challenging action shots. This helped make the transition to auto-focus easy and effective.

In my early 20s, personal growth led me to invest in a Nikon FG – my first SLR. It was a versatile tool that let me evolve from Program Auto Mode to Manual Settings. Determined to improve, I immersed myself completely into the world of photography including the purchase of a classic Speed Graphic 4 X 5 press camera, various medium format models, and enrolling in College Photography Programs.

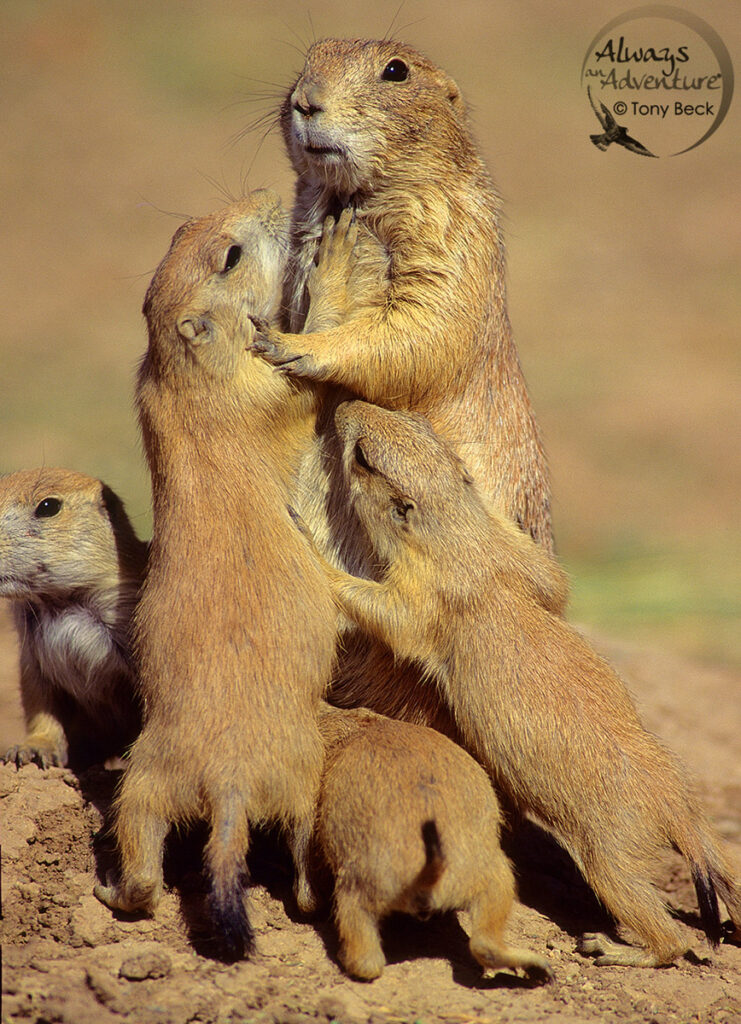

Although general photography was easy enough, wildlife photography proved to be extremely difficult. Capturing magazine-cover image quality of animals was impeded by the limitations of film and analog equipment.

Drake Northern Shoveler, Kodachrome 64 film – Texas – The Nikon FM2 was my favourite analog camera. Batteries were only needed for the camera’s meter – something I rarely used for wildlife. Most of the time, I would read the natural light and make my best guess as to what exposure would work. Bright, uninterrupted sunlight was always the easiest to work with, especially with the sun on my back.

Sadly, by the early 2000s, I regressed into a photographic rut. The joy of photography seemed to be waning. In the meantime, other photographers were discovering the conveniences of a new format – Digital Cameras. Because the first sensors produced low image quality, I resisted this new technology in favour of films like Kodachrome 25 and Velvia 50. As the millennium progressed, more amateurs got on the DSLR bandwagon. Some of them were achieving impressively high quality. So, to compete in the cut-throat world of photography, I had to get on board the digital trend.

In 2007, Nikon came out with the D300 complete with a CMOS sensor. With its reasonably fast & accurate autofocus and relatively good image quality, this camera was a game changer for me. From that point on, film became as useful as 8-track cassettes and rotary telephones.

Male Red-winged Blackbird on territory taken with Nikon Z9 mirrorless camera – Brighton, Ont.

Film processing required some patience. It took between an hour to a week before getting the results back. With its ability to immediately reveal results, digital cameras provide instant joy while also verifying the image’s sharpness, exposure, and composition. Immediately after completing a session of photographing any subject, I typically review the results to see if I’ve got the shots I want. This action of reviewing results in your digital camera is called “Chimping” – a very popular contemporary activity.

Since my first DSLR, I’ve worked with many digital cameras, each one improved over previous models.

Today, I work almost exclusively with mirrorless cameras. My most recent models include the Nikon Z8 and Z9 Mirrorless. They’re, without question, the best cameras I’ve ever had the pleasure of using. Lighter, faster, and easy to use, they have sophisticated autofocus with animal face recognition, accurate subject tracking, high frame rate, and all the other digital virtues expected in modern equipment. They make my success rate almost perfect.

Black-tailed Prairie Dogs mother and pups Tamron 400mm F4 on Nikon FM2 – Arizona – Working with analog cameras during frantic action proved to be extremely stressful. Stuck on 50 ISO at a slow 3.5 frames per second, the best results usually came with bright natural light and cooperative subjects. Changing film rolls during intense action was another stress maker. Fortunately, these Prairie Dogs continued their activity long enough to let me finish two rolls of film on the scene.

What improvements can we expect in the future? Eventually, I want a pocket-size camera that can produce superior-quality images of distant wildlife. It might take a while. But, I’m patient. The future of photography appears limitless.

Speed Graphic Press Camera – During my first years as a photography student, I bought several larger format models including a classic Speed Graphic Camera. It was slow and cumbersome. However, at 4 inches by 5 inches, the large film sheets produced spectacular image quality.

Thanks to Superior Photo at the Westgate Shopping Centre, Ottawa, for providing this vintage model camera.

Instamatic and Polaroid Cameras – These are two cameras I grew up with – Kodak Instamatic and Kodak Polaroid. They were simple and functional enough. However, they would never be as convenient as modern digital cameras, and they could never match their quality. Thanks to Superior Photo at the Westgate Shopping Centre, Ottawa, for providing these vintage model cameras.

Red Fox taken with Nikon Z9 mirrorless camera – Amherst Island, Ont. – Mirrorless models have many autofocus options including face recognition, even on animals. Accurate and fast, this feature alone has improved my success rate tremendously, even over most of my most recent DSLRs.

Crab Apple covered in ice after an ice storm taken with Fuji Velvia film – Ottawa, Ont. – To achieve marketable photos required working with slow ISO levels. The brightest colours and sharpest details could only happen with ISO levels of 25, 50, 64, or 100. This limitation forced many photographers to use tripods and methodical camera techniques. Under heavy overcast, a tripod was essential to capture a sharp image of these frosty crab apples.

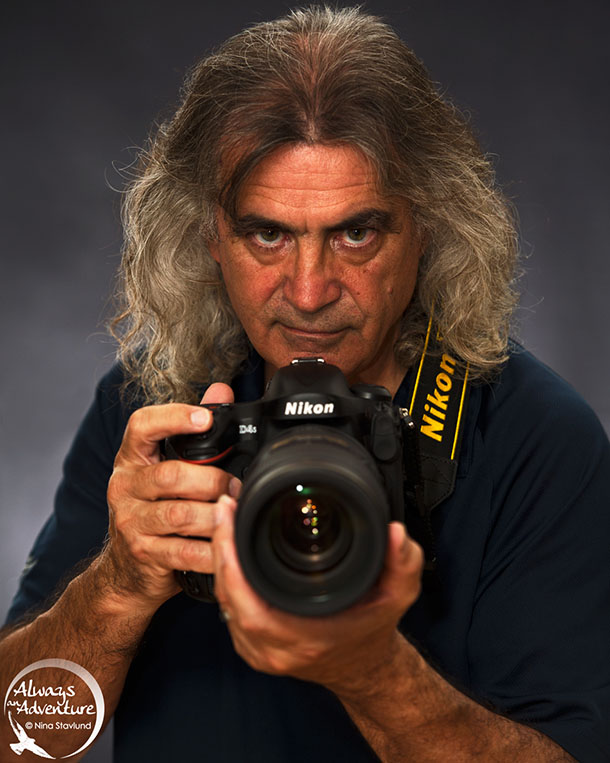

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Tony Beck is an award-winning, Nikon Ambassador, Vortex Ambassador, and freelance photographer based in Ottawa.

He teaches birdwatching and nature photography courses.

Follow Tony’s adventures at www.AlwaysAnAdventure.ca