Article by Dimitri Papatheodorou

John Berger wrote eloquently on photography; he passed away in January of this year at age 90. Perhaps he, better than anyone, was able to explain concisely why photography can be fine art:

John Berger wrote eloquently on photography; he passed away in January of this year at age 90. Perhaps he, better than anyone, was able to explain concisely why photography can be fine art:Photographs bear witness to a human choice being exercised in a given situation. A photograph is a result of the photographer’s decision that it is worth recording that this particular event or this particular object has been seen. If everything that existed were continually being photographed, every photograph would become meaningless.

Berger explained why artists like Gary Mulcahey are worth looking at: What distinguishes the one [photograph] from the other is the degree to which… the photograph makes the photographer’s decision transparent and comprehensible. Thus we come to (the) little understood paradox of the photograph. The photograph is an automatic record through the mediation of light of a given event: yet it uses the given event to explain its recording. Photography is the process of rendering observation self-conscious. The type of photography Berger describes above is the kind of artwork Mulcahey has been practicing for so long. It is the kind of picture making that amateur artists may try to achieve, a technique that surely can’t be taught but when mastered can become as automatic as brushing your teeth or driving a car. Mulcahey doesn’t explain his process, but what we see in these FARM(er) photographs, is realism at play.

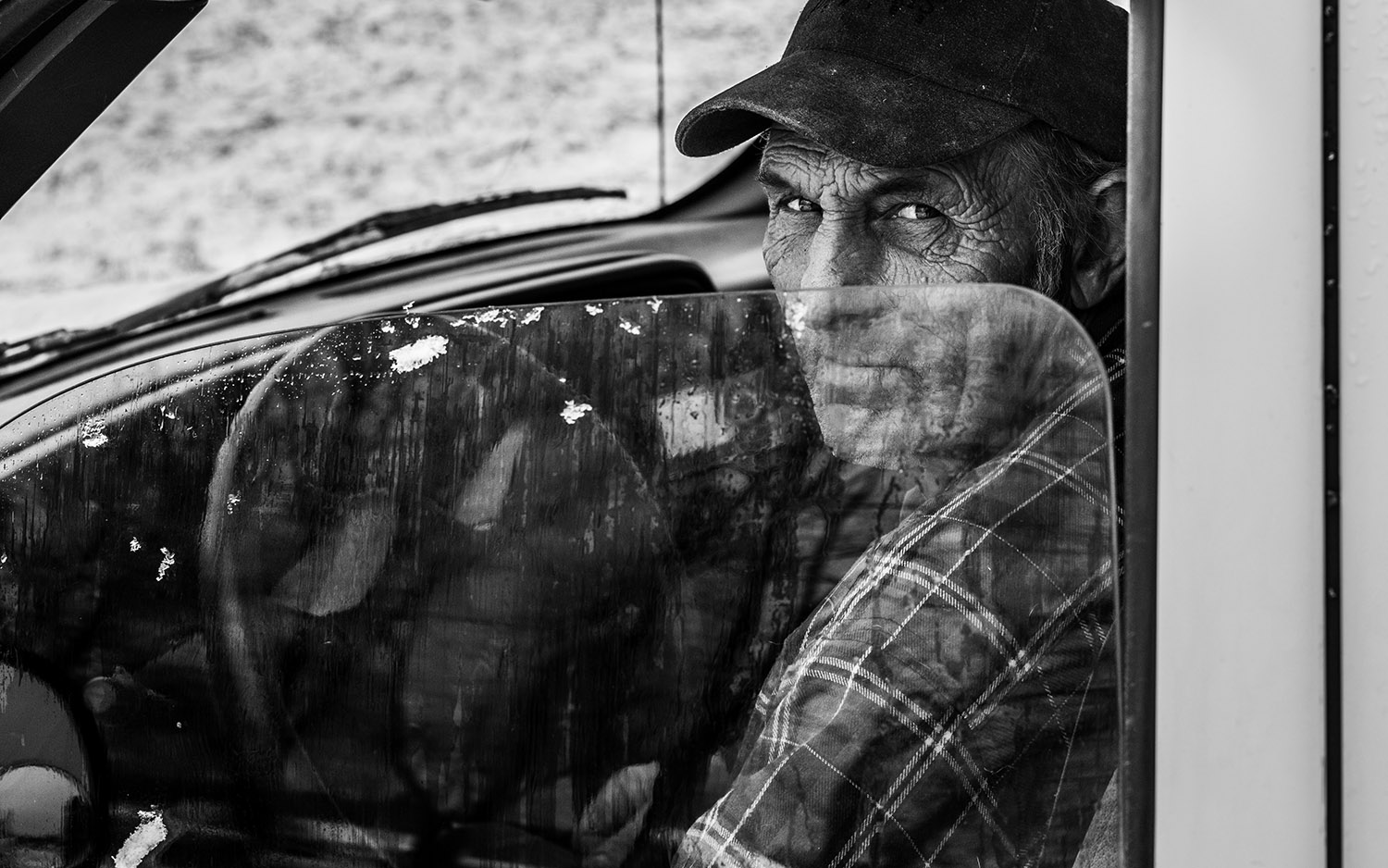

These images resonate with us. In the photograph ‘Man Looking Back from Window’ (my title not his), Mulcahey captures a local farmer in real time. His truck is stationary but there is a feeling he is going somewhere; this invites us to enter into the story of what might be happening. We don’t see his dying dog seated beside him, we only see the immediate emotional impact of pending loss. The moment is made more poignant by seeing his backward glance and weathered features through rain-streaked glass. It is through a slight shift in time, the time between Mulcahey’s choosing to snap the picture and the actual moment of capture, that objective reality is rendered. The separation between Mulcahey and his subject is like an invisible picture frame – a moment of clarity and decision-making. Most pictures are not taken with this intent. Indeed, most pictures represent collapsed or flattened time, and are therefore subjective. In every day photo making, the photographer and the person being photographed are bound together in a combined moment. There is usually no separation between the two. Separation and distance makes a significant difference when practicing the art of photography, as opposed to merely snapping a picture. Certainly, there are other artistic issues, like composition, light and dark, line, texture and so on, but these are all things that are more easily both taught and learned. In each of Mulcahey’s ‘decisions’ (to coin John Berger) we see people rendered as they are. The artist does not make something of the subject through placement and pose. He does not invent a persona or set the stage for life’s drama. He captures the person in the most powerful and real way, expressed visually.

Gary Mulcahey’s FARM[er] Portraits of Nothumberland County Family Farms will be exhibited April 1 to 30, 2017 at the Ah! Arts & Heritage Centre, Warkworth, ON For more information, please contact info@ahcentre.ca – www.ahcentre.ca

Gary’s Bio:

Gary Mulcahey is a full-time practicing photographer. His current professional focus is to build a body of work in documentary photography. His work since 2012 focuses on portrait photography in the field documenting people in their rural, remote and indigenous communities. The portraits aim to photographically and artistically place people in a physical as well as a social and historical context. The resulting images highlight the interaction of culture, industry, geography and lived community experience that is imprinted on their faces.