The birth of an aurora begins 150 million kilometres away, on the torrid surface of the sun. There, continuous gigantic explosions, called sunspots, send showers of charged particles, (electrons and protons) hurtling into space and racing towards Earth, sometimes nearly at the speed of light. Usually it takes 30 minutes to two days for the particles to reach our planet, but Earth is not an easy target to penetrate.

Surrounding Earth is a giant invisible magnetic field generated by the molten metals in the planet’s core. Most of the charged particles speeding toward us from the sun are deflected away into space by the force of the Earth’s magnetic field. Some, however, penetrate the field, and once they reach the upper layers of our atmosphere, they collide with the gases there, producing visible light. The same thing happens in an ordinary neon sign: electrons collide with the neon gas trapped inside the light tube, and the gas emits a reddish orange light.

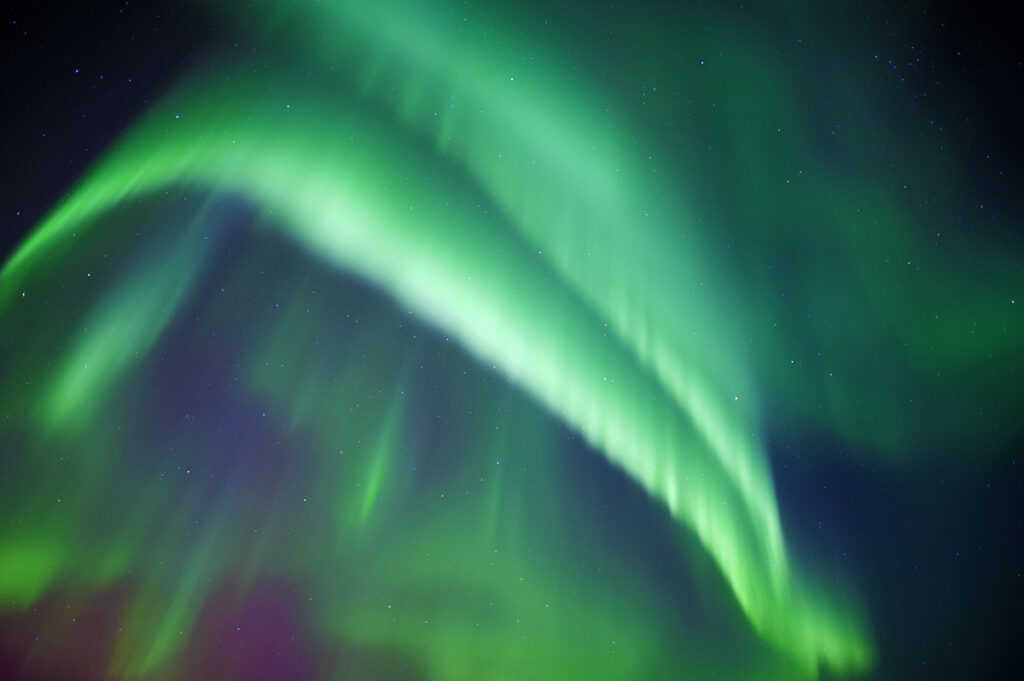

An aurora can take many different forms. It may simply be a diffuse glow covering the whole sky; at such times, it can be confused with thin, wispy clouds. A common auroral display is a narrow arc that can stretch across the sky for 1,600 kilometres. The most beautiful auroras are those in which curtains of shimmering light fold and spiral unpredictably across the velvet blackness, constantly changing in colour, brightness and speed.

When viewed from space, an aurora forms a bright crown of light encircling the northern polar region. Yellowknife lies under the magical Auroral Oval where northern lights occur on 90 percent of nights. Of course, seeing the aurora requires a cloudless, black sky. Auroras are most intense around the autumn and spring equinoxes, so September and March are especially good months for such a photo quest.

Here are a few photo tips to help you capture the beauty of the aurora. A sturdy tripod is a must since long exposures are a necessity to photograph the night sky. For lenses, I suggest you use the fastest wide angle lens you can get your hands on. Since the aurora often stretches across the entire sky you need the coverage of a wide angle lens to capture the graceful arcs and swirls of the display. Focal lengths of *12mm to *35 mm are ideal. The maximum aperture of the lens is just as important as the focal length since the aperture will ultimately determine the shutter speeds you will use.

(*@editor – check out Laowa’s super-fast wide angle Argus lenses and the whole line of wide angle landscape lenses)

During long shutter speeds, say 30 to 60 seconds, the stars move. During such lengthy exposures, the stars may register as streaks of light, called star trails, instead of pin-point sources of brightness. An easy formula to avoid this from happening is to divide 600 by the focal length of the lens. This calculation yields the maximum shutter speed (in seconds) that you should use if you want to avoid star trails. For example I commonly use a 24mm lens and I keep my shutter speeds shorter than 25 seconds (calculated by dividing 24 into 600). The 24mm lens I use has a maximum aperture of f1.4. By varying the ISO sensitivity of the camera’s sensor between 800 and 1600 I am usually able to capture even the faintest of auroras with shutter speeds below the prescribed maximum of 25 seconds.

Surprisingly, focusing the aurora is another issue. Typically, you can’t use autofocus because the aurora in a blackened night sky doesn’t provide enough contrast for the camera to detect. That’s easy to solve you say, just manually set the lens on infinity. But notice that many lenses focus a little beyond infinity and this is meant to compensate for the slight shrinkage and expansion of glass lenses as the temperature varies. So, setting the lens at infinity may yield a slightly soft photograph. Here is the solution I recommend. If you own a camera with live view, position a bright star in the centre of the camera’s LCD screen, zoom to 10 power, then manually rotate the focusing ring until the star is a pin point of light without a halo around it. If your camera doesn’t have live view capability then you should take successive photographs of the same star, tweaking the focusing repeatedly and then checking the results in your LCD screen until the star is a pin point.

Sunspot activity roughly follows an 11-year cycle. The next solar maximum is expected in July 2025 with a peak of 115 sunspots. Now is a good time to practice and get ready.

About the Author – Dr. Wayne Lynch

For more than 40 years, Dr. Wayne Lynch has been writing about and photographing the wildlands of the world from the stark beauty of the Arctic and Antarctic to the lush rainforests of the tropics. Today, he is one of Canada’s best-known and most widely published nature writers and wildlife photographers. His photo credits include hundreds of magazine covers, thousands of calendar shots, and tens of thousands of images published in over 80 countries. He is also the author/photographer of more than 45 books for children as well as over 20 highly acclaimed natural history books for adults including Windswept: A Passionate View of the Prairie Grasslands; Penguins of the World; Bears: Monarchs of the Northern Wilderness; A is for Arctic: Natural Wonders of a Polar World; Wild Birds Across the Prairies; Planet Arctic: Life at the Top of the World; The Great Northern Kingdom: Life in the Boreal Forest; Owls of the United States and Canada: A Complete Guide to their Biology and Behavior; Penguins: The World’s Coolest Birds; Galapagos: A Traveler’s Introduction; A Celebration of Prairie Birds; and Bears of the North: A Year Inside Their Worlds. In 2022, he released Wildlife of the Rockies for Kids, and Loons: Treasured Symbols of the North. His books have won multiple awards and have been described as “a magical combination of words and images.”

Dr. Lynch has observed and photographed wildlife in over 70 countries and is a Fellow of the internationally recognized Explorers Club, headquartered in New York City. A Fellow is someone who has actively participated in exploration or has substantially enlarged the scope of human knowledge through scientific achievements and published reports, books, and articles. In 1997, Dr. Lynch was elected as a Fellow to the Arctic Institute of North America in recognition of his contributions to the knowledge of polar and subpolar regions. And since 1996 his biography has been included in Canada’s Who’s Who.