Since childhood, I’ve been an enthusiastic bird nerd, and one of the first exotic birds I identified was a boreal owl. Since then, I have seen all 19 species of owls found in Canada and the United States. It’s common, however, to meet people who have never seen an owl in their life, and if they have, it is usually one or more of the larger species. Even though owls are rarely seen, many people appreciate and value them greatly, so much so that three species of owls in Canada are official provincial avian emblems. In Alberta, it’s the great horned owl, in Manitoba it’s the great gray owl, and in Quebec the snowy owl. All three are among the largest owl species in our country.

Not all owls are large and conspicuous. In fact, half of the 19 kinds in Canada and the US are small (<23cm/9in tall), secretive, forest birds, hunting mostly at night and always nesting in abandoned woodpecker holes or natural tree cavities. Their small size makes them extremely vulnerable to attack from the larger owl species as well as from daytime-hunting hawks and eagles so they need to stay hidden as much as possible.

Below is a gallery of some of these small, secretive owls.

The ferruginous pygmy-owl inhabits semi-arid desert scrub and mesquite woodlands in a small area of southern Arizona. It feeds largely on insects and lizards.

When it comes to audacity and rapaciousness, the northern pygmy-owl displays the heart of a lion in a body smaller than a blue jay. Few songbirds are safe in the hunting territory of this pygmy-owl. There is even a record of an ambitious northern pygmy-owl attacking a 2.7- kg (6-lb) barnyard chicken—a 38-fold difference in weight between predator and prey. A biologist friend of mine, Dr. Gordon Court, jokes that if “pygmy-owls were as big as beavers, cows wouldn’t be safe.”

In addition to songbirds, the northern pygmy-owl also hunts small mammals, lizards, and a wide range of insects, including butterflies, moths, dragonflies, crickets, and cicadas. In this case the owl has caught a meadow vole.

The boreal owl ranges the farthest north of any of the small owls in North America, extending to the boundary between the boreal forest and the Arctic tundra at a latitude of 67° north in Alaska.

The boreal owl relies heavily on hearing to detect its prey, perching just two meters (6 ft.) above the ground when hunting. They are impatient hunters, changing perches frequently, often every 2 to 4 minutes.

Boreal owls lay 3-5 eggs. Typically the chicks roost separately as soon as they leave the nest cavity. The chicks pictured here were temporarily placed on a stump by the biologist who was banding them.

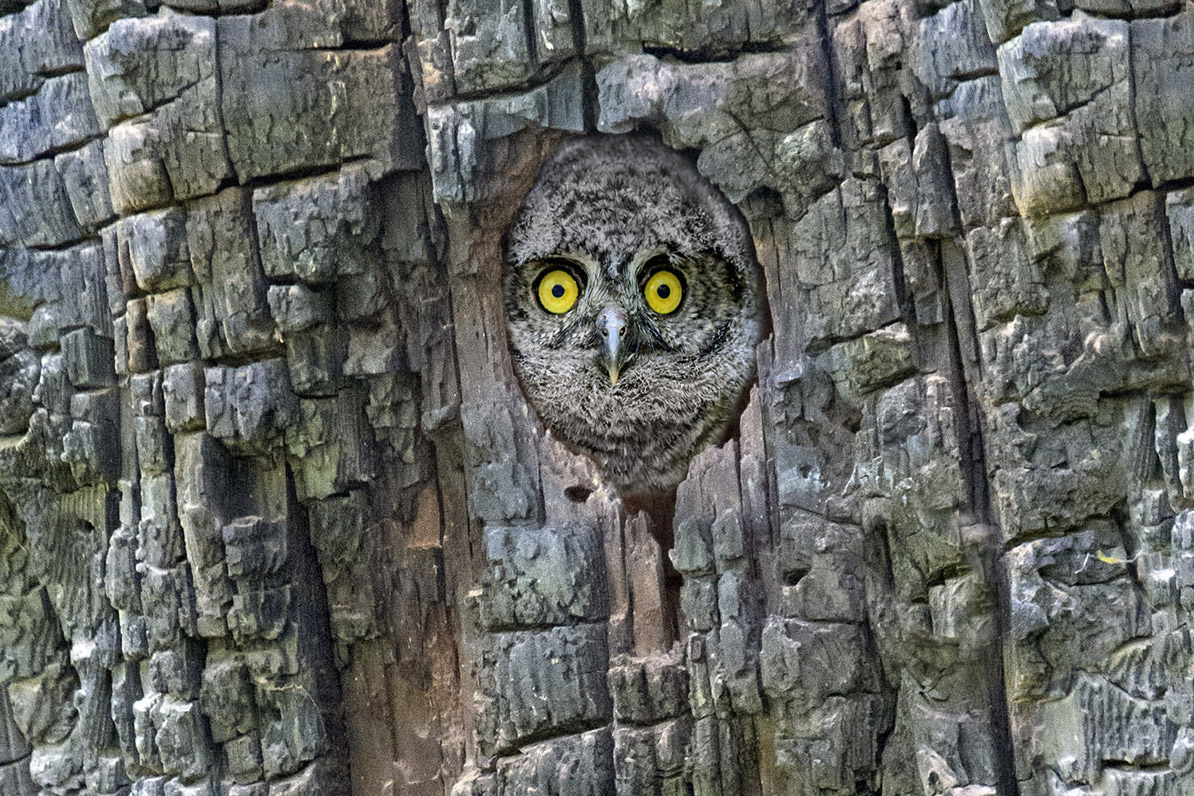

All owls hatch with a coat of whitish down. Within a few weeks the natal coat is replaced by a second downy coat that is distinctive for each species. That of the western screech-owl is gray with wavy black streaks.

Many saw-whet owls that live in the northern parts of their range migrate south in the winter. The owl pictured here had established itself at a residential bird feeder and was preying on the local redpolls and chickadees.

The downy feathers of a northern saw-whet chick are quite different than those of the western screech-owl pictured earlier.

The eastern screech-owl occurs in two colour variations: gray and rufous, the latter being most common in the eastern United States. The owl pictured here was photographed in central Florida.

These western screech-owl chicks were huddled together next to a tree trunk where their cryptic plumage matched the coloration of the bark, making them less conspicuous.

This hungry western screech-owl chick was peeking out of the family nest hole waiting for a parent to deliver dinner.

The 18-cm (7-in) tall flammulated owl is the second smallest owl in North America. It feeds exclusively on insects, in particular moths and beetles, and as a result is forced to migrate south to Mexico every winter when flying insects disappear.

The flammulated owl’s hoots are well known for their low frequency and their ventriloquistic character, which makes the bird difficult to pinpoint. Being a ventriloquist may help the tiny owl hide its location from larger owls that might prey on it.

This whiskered screech-owl in Arizona had heard some leaves rustle and was intently searching the ground for a potential meal. The owl preys on beetles, grasshoppers, mole crickets, and other insects.

The 15-centimeter (6-inch) tall sparrow-size elf owl is the smallest owl in the world. It occurs in the desert regions of the southern United States. Abandoned woodpecker holes in saguaro cactuses are a common place for elf owls to roost and nest.

The first step in successfully photographing owls is to find them. A few years ago, I wrote a book about owls, which was published by Johns Hopkins University Press. At the end of the book, I gave readers some tips for finding owls that I hope you will find helpful.

Boreal Owl

Tip #1 Load an App and Scroll a Website

Cornell University offers a free birdwatching app called Merlin (merlin.allaboutbirds.org).You can download bird packs for almost every region on the planet. For each bird you get basic ID information and photos, their calls, and a range map. The app will also help you identify the bird calls you may not recognise. The app is an invaluable tool, and it’s free.

The gold standard of birdwatching websites is ebird.org. You can scroll through the daily sightings by local birdwatchers in your area to learn if the owl species that interests you has been seen lately and where the sighting occurred. Two winters ago a rare boreal owl showed up in an urban park in Calgary. I learned about it from regularly scrolling through ebird to see which rarities had recently been seen.

Blue jay

Tip #2 Listen for Bird Calls

During the day, many owls, especially the smaller ones such as northern saw-whets, boreals, and pygmy owls, roost in thick shrubbery or bushy conifers. If a foraging blue jay, chickadee, or redpoll locates one of these hidden owls, they chatter and chirp excitedly. Their noisy alarm calls summon other songbirds that may be nearby to come and mob the owl. I have found many owls by listening for these calls. It’s not hard to recognize the agitated scream of a blue jay. Even an amateur birdwatcher can detect the excitement in the bird’s voice. This particular blue jay alerted me to a barred owl hidden in a spruce tree.

Snowy owl pellet

Tip #3 Prospect for pellets and poop

Many owls use the same roost trees day after day. The branches and the ground underneath become soiled with conspicuous white droppings. In winter, long-eared owls commonly roost in groups, and several dozen owls may shelter in such roosts, making the droppings easy to spot.

Frequently, the ground below a roost site is also littered with pellets—those compact, cigar-shaped wads of undigested bones, teeth, and fur that owls regularly regurgitate.

The photo above is of a pellet regurgitated by a snowy owl that was regularly using a winter roost in southern Alberta.

Long-eared owl

Tip #4 Cruise the roads.

I am most successful at finding some of the larger species of owls by slowly driving along highways and back roads, especially in winter when the leaves have fallen. Great gray owls, northern hawk owls, and snowy owls frequently hunt voles and mice in the ditches alongside roadways. These large conspicuous owls are fairly easy to locate. In some years, they literally flood into the forests and prairies of southern Canada and the northern United States, and they stay throughout the winter. This occurs roughly every three to five years when rodent populations in the boreal forest or the Arctic crash, compelling the owls to move south.

Driving the roads is also the best way I know to find nesting great horned owls. Where I live in southern Alberta, these large owls are the first birds to nest in spring, often starting to lay eggs in the early days of March, long before the end of winter. Typically, great horned owls use the old stick nests of crows and hawks, and the owl’s distinctive feathery ear tufts can be seen sticking above the rim of the nests from several hundred yards away. On a Sunday drive in March, armed with binoculars and a spotting scope, I can often find 3 or 4 nesting great horned owls in the aspen woodlands around Calgary.

Sometimes a drive can yield an unusual owl sighting. One afternoon, I found a long-eared owl (pictured above) in broad daylight sitting on a fencepost just 15 meters (50 feet) from the edge of a gravel road. Typically, long-eared owls are strictly nocturnal and highly secretive. I know that, but apparently the owl didn’t. It was hunting voles in the ditch and I watched it at close range for more than an hour. It completely ignored my vehicle the whole time.

About the Author – Dr. Wayne Lynch

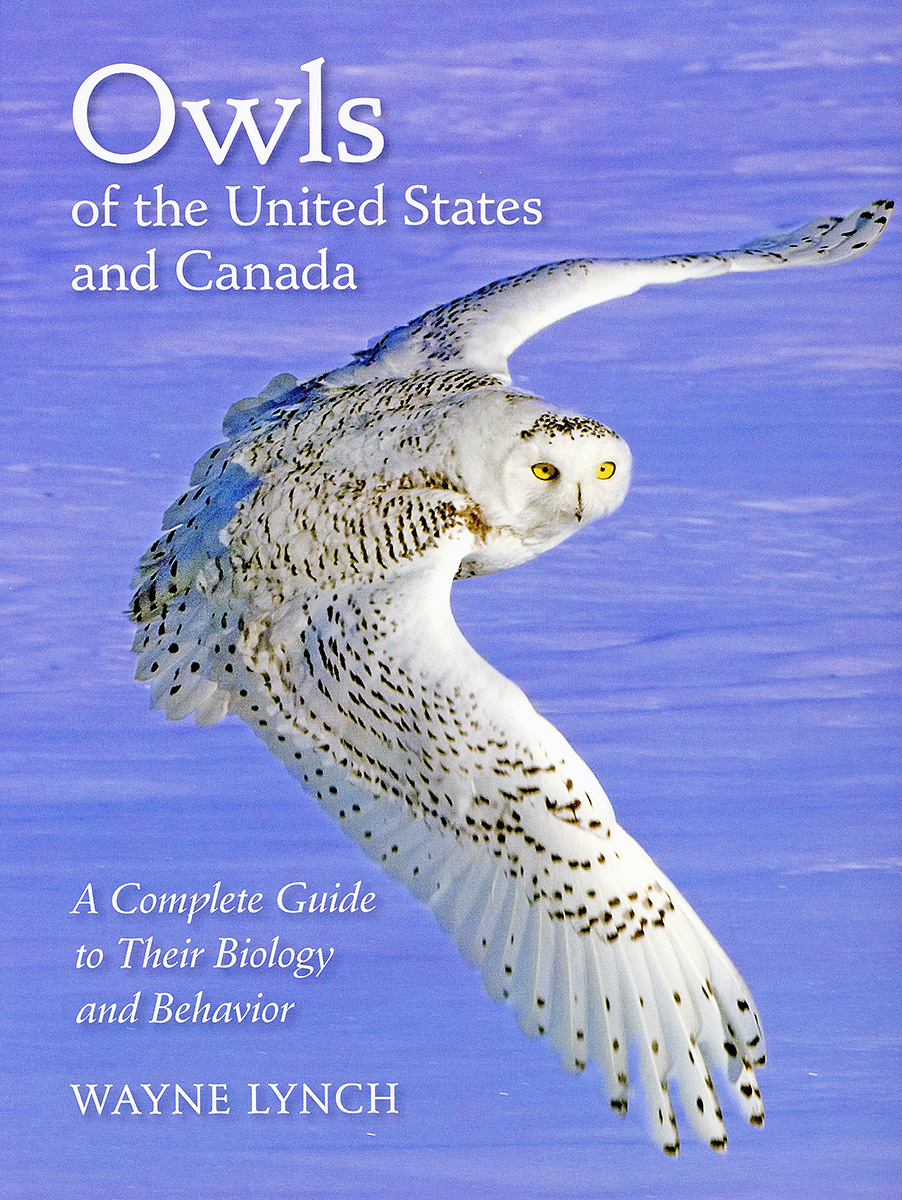

For more than 40 years, Dr. Wayne Lynch has been writing about and photographing the wildlands of the world from the stark beauty of the Arctic and Antarctic to the lush rainforests of the tropics. Today, he is one of Canada’s best-known and most widely published nature writers and wildlife photographers. His photo credits include hundreds of magazine covers, thousands of calendar shots, and tens of thousands of images published in over 80 countries. He is also the author/photographer of more than 45 books for children as well as over 20 highly acclaimed natural history books for adults including Windswept: A Passionate View of the Prairie Grasslands; Penguins of the World; Bears: Monarchs of the Northern Wilderness; A is for Arctic: Natural Wonders of a Polar World; Wild Birds Across the Prairies; Planet Arctic: Life at the Top of the World; The Great Northern Kingdom: Life in the Boreal Forest; Owls of the United States and Canada: A Complete Guide to their Biology and Behavior; Penguins: The World’s Coolest Birds; Galapagos: A Traveler’s Introduction; A Celebration of Prairie Birds; and Bears of the North: A Year Inside Their Worlds. In 2022, he released Wildlife of the Rockies for Kids, and Loons: Treasured Symbols of the North. His books have won multiple awards and have been described as “a magical combination of words and images.”

Dr. Lynch has observed and photographed wildlife in over 70 countries and is a Fellow of the internationally recognized Explorers Club, headquartered in New York City. A Fellow is someone who has actively participated in exploration or has substantially enlarged the scope of human knowledge through scientific achievements and published reports, books, and articles. In 1997, Dr. Lynch was elected as a Fellow to the Arctic Institute of North America in recognition of his contributions to the knowledge of polar and subpolar regions. And since 1996 his biography has been included in Canada’s Who’s Who.